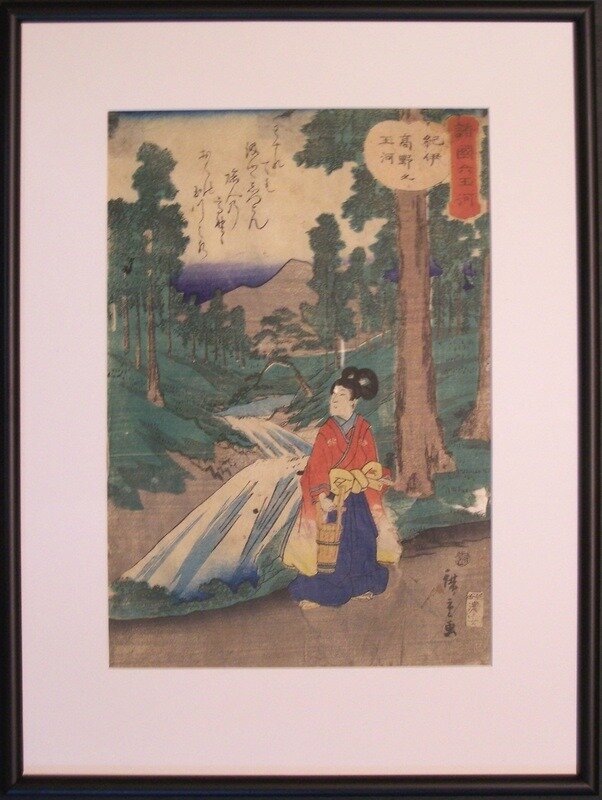

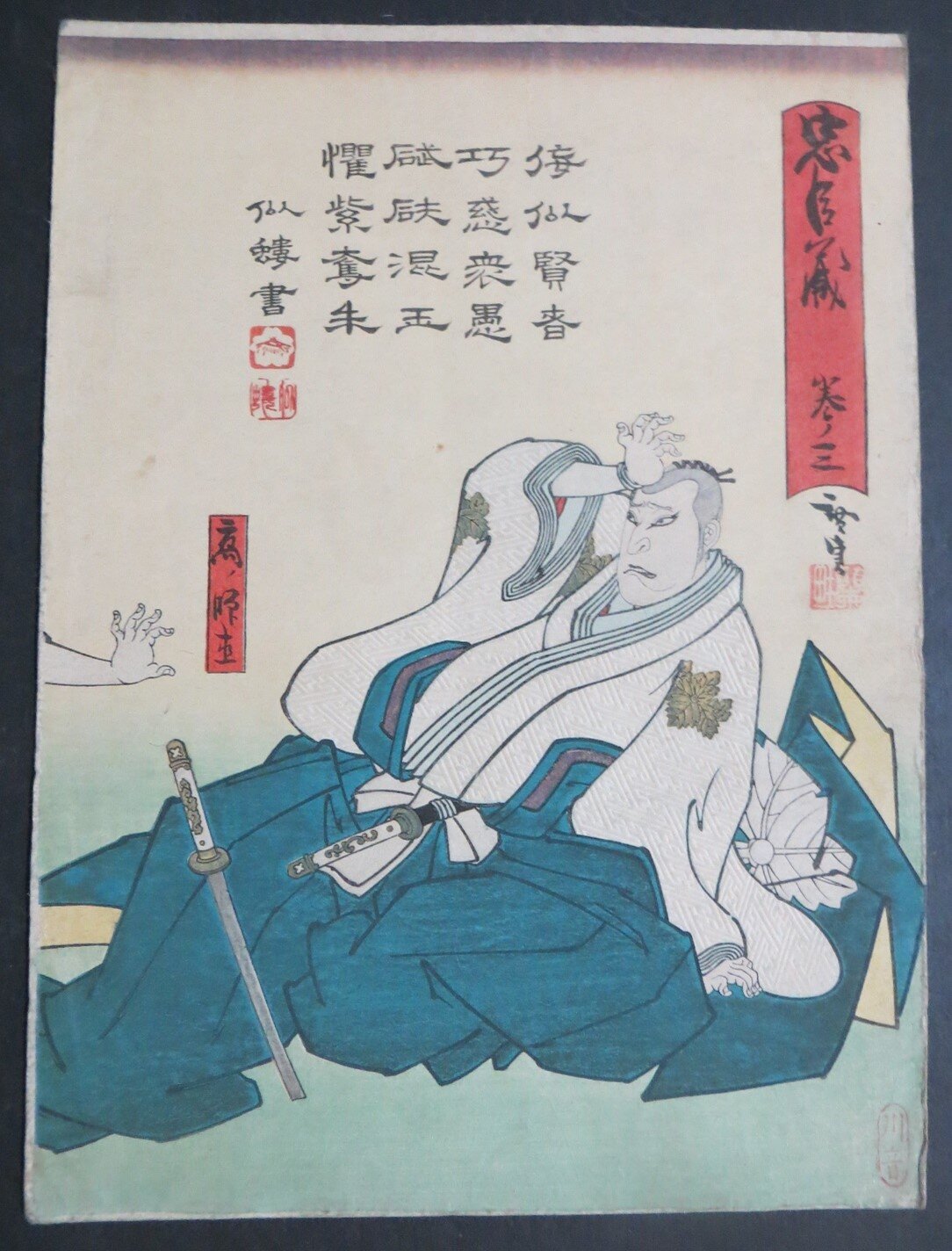

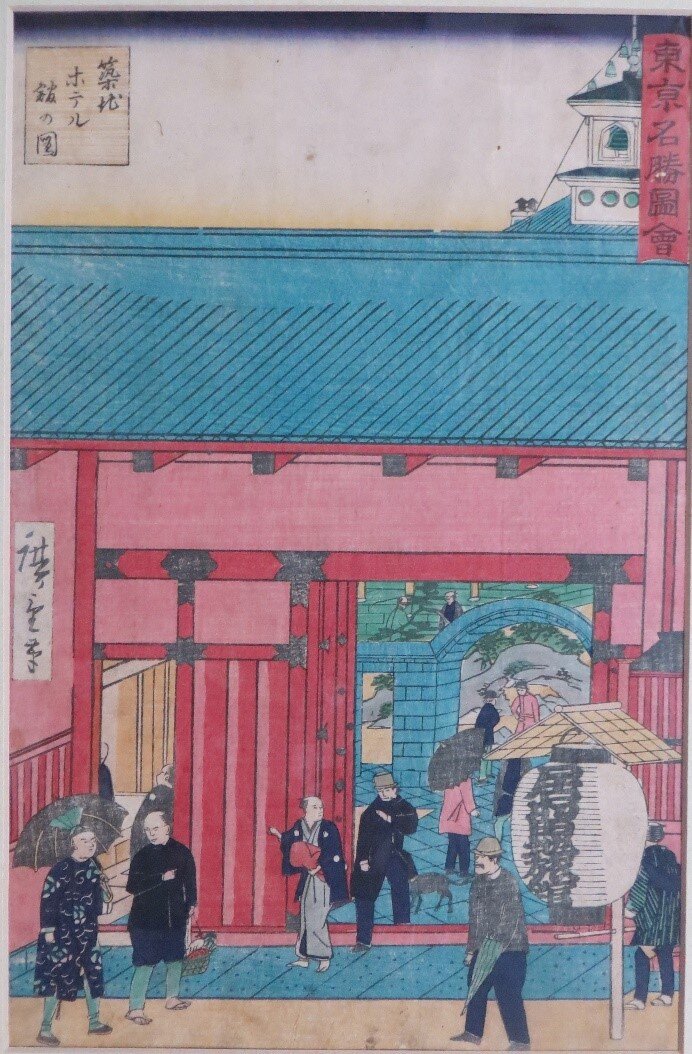

Japanese Wood block Print

After technological advances in the 18th century enabled printing in full color, woodblock printing as an artistic medium began in earnest. Printmakers who had previously produced monochromatic manuscripts were now able to create polychrome prints and elaborately illustrated calendars for wealthy patrons. While woodblock prints are often attributed to a single artist, the actual prints often represent the combined efforts of four specialists: the designer, the engraver, the printer, and the publisher. The designer, who would have his signature on the finished print, would first execute a drawing or painting, The engraver then took over and traced the original drawing to create a negative, in a series of woodblocks used for printing. Polychromatic prints sometimes required as many as 20 separate woodblocks. The printer or printers coated the block and laid a piece of paper on top of the block to generate an impression. The finished print was later distributed for sale by the publisher. From the 17th to 19th centuries, the Ukiyo-e school of art flourished in Japan. During this period, the name of which translates to “pictures of the floating world,” many of today’s most renowned Japanese woodblock printers rose to prominence. The late 18th century is considered the golden age of Japanese woodblocks due to the wealth of artistic talent and a shift in popular subject matter. Woodblock prints of the Edo period (1615-1868) characteristically featured sumo wrestlers, famous Kabuki actors, and geisha performers. In the late 18th century, this style of portraiture declined in popularity, replaced by a demand for romanticized landscapes and depictions of notable historical scenes.